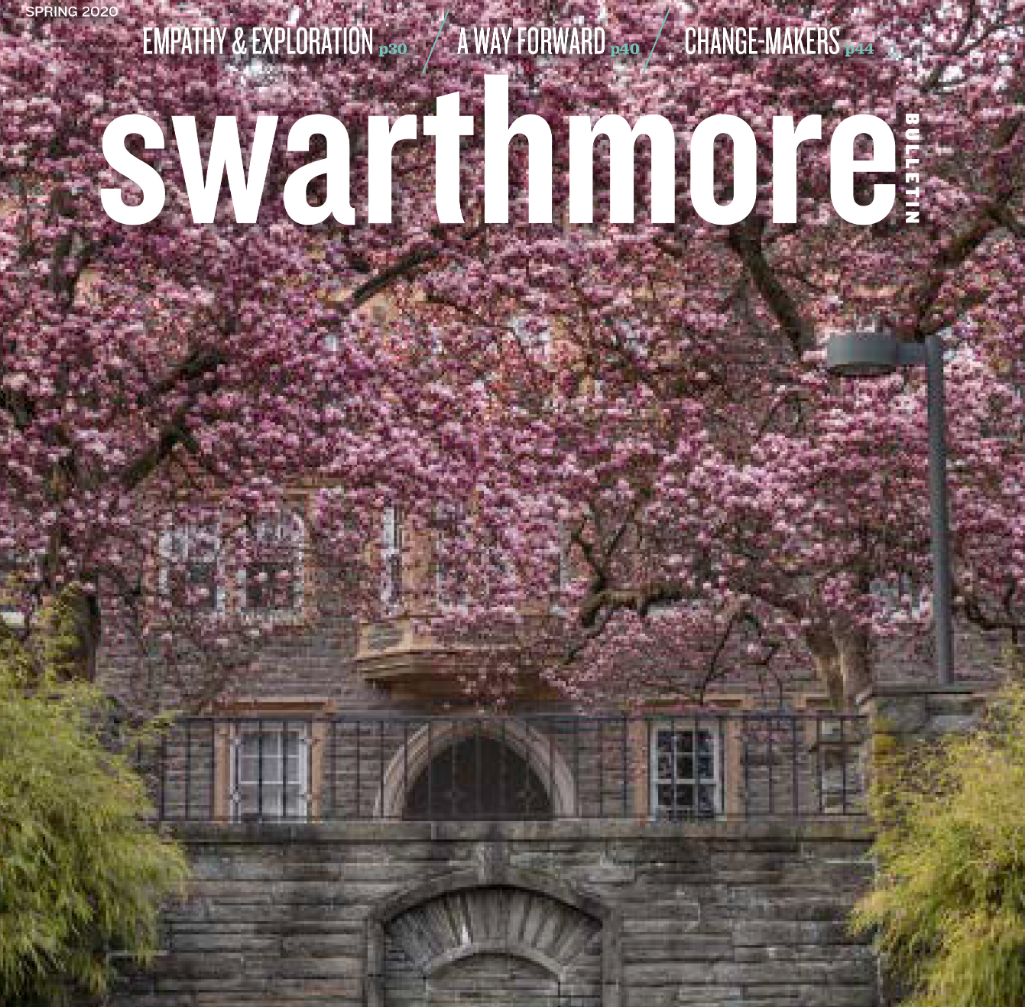

[APR 2020]

Honoring Ingenuity – Swarthmore College Bulletin

Highlights the five female faculty members at Swarthmore College in the sciences who recently received major federal grants, including Eva-Maria Collins.

“Five female faculty members in the sciences recently received major federal grants, highlighting the ingenuity and passion for learning that courses through the College. Among them are Cacey Bester, assistant professor of physics, and Amy Graves, Walter Kemp Professor in the Natural Sciences and professor of physics — the newest and longest-serving members of the department, respectively. They will support the efforts of Bucknell University physicists Brian Utter and Katharina Vollmayr-Lee on a three-year, $600,000 grant from the National Science Foundation to study properties of granular materials. The project aligns Bester’s experimentalist approach with Graves’s computer simulations. Their Research in Undergraduate Institutions award will fund student …”

[FEB 11, 2020]

Five Women in the Sciences Receive Major Federal Grants

Three Swarthmore faculty earned a grant from the National Institutes of Health (NIH) Academic Research Enhancement Awards program. Eva-Maria Collins earned a grant from the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences for a two-year study on the impact of pesticides on developing brains.

[JAN 13, 2020]

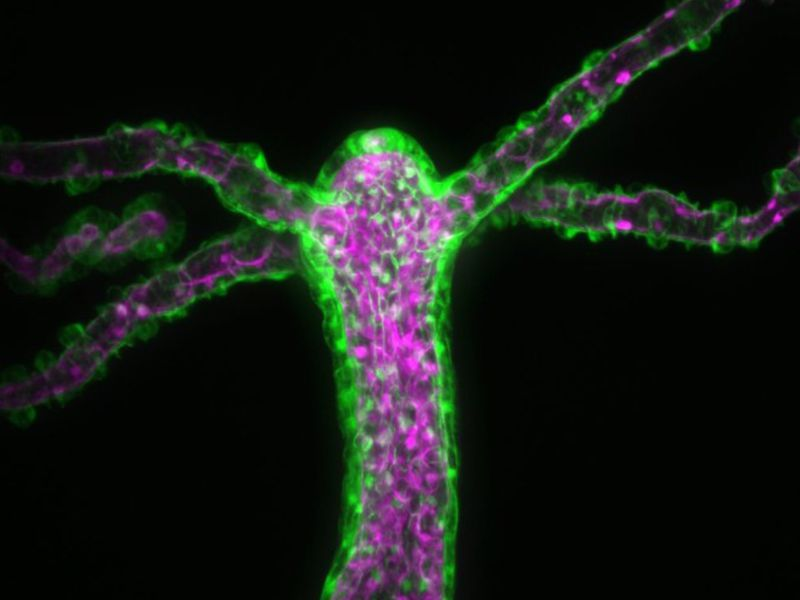

Listen: Biologist Eva-Maria Collins on the Real-Life Hydra

In the fall, Associate Professor of Biology Eva-Maria Collins delivered “The Serpent’s Maw: A Physics Perspective on Mouth Function and the Dynamics of Hydra Regeneration,” a lecture in the physics colloquium series.

[AUG 2019]

Board of Publications Toxicological Sciences Paper of the Year Award

The “Toxicological Sciences Paper of the year 2019” was awarded by the Society of Toxicology to the paper

“There are ongoing efforts to devise new screening models to predict toxicity and potentially prioritize chemicals that might influence development. Hagstrom and colleagues compared two models that utilized aquatic species to examine developmental neurotoxicity by compounds in a chemical library. An interesting aspect of these models is that they span a spectrum of events associated with development, allowing for breadth of analyses and the relatively short period of time to observe effects. Results from these analyses demonstrated that the models provided a high degree of predictability based on examination of known developmental neurotoxicants. This work illustrates the effective utility and potential future application of a model that can be used for screening large chemical libraries to mechanistically evaluate potential developmental neurotoxicants. This well-written manuscript has made a significant positive impact to the field of toxicology. The Board of Publications proudly confers the Paper of the Year Award to Dr. Collins and her research team.”

[JUL 11, 2019]

Trilateral Science Slam in Tucson, AZ

Rui Wang won the third Trilateral Science Slam, in which 6 “slammers” from Germany, Russia and the USA participated.

“And the winner is… Rui Wang! With her genuine fascination (which, by the way, carried over to the Saguaro cacti she saw in Tucson) and quirky, deadpan humor, Rui struck just the right balance between the fantastic and the scientific to win over the audience. It was a tight competition, as audience applause varied only slightly for each of the superbly done slams, but Rui nudged out the others with her brand of earnest, clearly articulated, no-nonsense science and her straight-faced, somewhat irreverent, at times morbid amusement, winning over a crowd half-composed of physicists, chemists, astronomers and Fulbright-Cottrell Scholars attending the Cottrell Scholar Conference at the resort. And in doing so secured a first American victory for this third trilateral science slam!”

[SEP 25, 2017]

Researchers explain the mechanism of asexual reproduction in flatworms – Phys.org

Coverage of the PNAS article Malinowski et al.: “Mechanics dictate where and how freshwater planarians fission.“

“Freshwater planarians, found around the world and commonly known as “flatworms,” are famous for their regenerative prowess. Through a process called “fission,” planarians can reproduce asexually by simply tearing themselves into two pieces—a head and a tail—which then go on to form two new worms within about a week. When, where and how this process unfolds has remained a puzzle for centuries due to the difficulty of studying fission. But now, a team of University of California San Diego scientists provides a new biomechanical explanation in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS). Planarians are notoriously difficult to study. They do not like to be watched during fission, which primarily happens in the dark and halts at the slightest disturbance…”

[SEP 25, 2017]

Mechanism of asexual reproduction in flatworms – Science Daily

Coverage of the PNAS article Malinowski et al.: “Mechanics dictate where and how freshwater planarians fission.“

[MAR 11, 2016]

Gaze Into the Disappearing Mouth of the Hydra – HowStuffWorks

HowStuffWorks video covering the findings of the Biophysical Journal publication – Carter and Hyland et al.: “Dynamics of Mouth Opening in Hydra“.

[MAR 10, 2016]

How Hydra Rip Open New Mouths at Every Meal – Smithsonian Magazine

Coverage of the Biophysical Journal publication – Carter and Hyland et al.: “Dynamics of Mouth Opening in Hydra“.

“Hydra are infamous for their ability to regenerate tissue after being torn apart. But one mystery about these tiny tentacled creatures that has dogged scientists was: How do Hydra open their mouths? Biologists have long known that Hydra do not have a permanent mouth, writes Rachel Feltman for The Washington Post. Each time the animal needs to feed, its skin cells separate to form an opening. Soon after ingesting its dinner, the proto-mouth closes back up…”

[MAR 9, 2016]

The Hydra Gets a New Mouth With Every Meal – The New York Times

Coverage of the Biophysical Journal publication – Carter and Hyland et al.: “Dynamics of Mouth Opening in Hydra“.

“This week’s GIF science lesson might give you a newfound appreciation for how simple it is for most humans to consume a shrimp cocktail. No, this tiny aquatic creature is not that multi-headed sea beast of Greek mythology that regenerates a head every time some daring hero chops it off. It doesn’t even have a head. But like the mythical hydra, the real hydra does regenerate, which is why scientists have been studying it for decades. Over time, researchers have learned one fact creepy enough to fuel nightmares: Every time this pond-dweller wants to eat — for example a little brine shrimp — it rips a hole through the center of its body’s outer layer. When dinner is done, it closes back up…”

[MAR 8, 2016]

Inside the Mouth of a Hydra – Cell Press

Coverage of the Biophysical Journal publication – Carter and Hyland et al.: “Dynamics of Mouth Opening in Hydra“.

“Hydra is a genus of tiny freshwater animals that catch and sting prey using a ring of tentacles. But before a hydra can eat, it has to rip its own skin apart just to open its mouth. Scientists reporting March 8 in Biophysical Journal now illustrate the biomechanics of this process for the first time and find that a hydra’s cells stretch to split apart in a dramatic deformation…”

[MAR 8, 2016]

Here’s how the hydra rips its own body open to eat a meal – Washington Post

Coverage of the Biophysical Journal publication – Carter and Hyland et al.: “Dynamics of Mouth Opening in Hydra“.